- Home

- Tony Iommi

Iron Man Page 9

Iron Man Read online

Page 9

We all played ‘Sweet Leaf ’ while stoned, as at that time we were doing a lot of dope. While I was recording an acoustic guitar bit for one of the other songs, Ozzy brought me a bloody big joint. He said: ‘Just have a toke on this one.’

I went: ‘No, no.’

But I did, and it bloody choked me. I coughed my head off, they taped that and we used it on the beginning of ‘Sweet Leaf’. How appropriate: coughing your way into a song about marijuana . . . and the finest vocal performance of my entire career!

‘Into The Void’ is one of my favourite songs from that line-up; ‘Sabbath Bloody Sabbath’ is my other one. The structure of those songs is really good, because they have lots of different colours, there’s lots of different stuff happening in them. ‘Into The Void’ has this initial riff that changes tempos in the song. I like that. I like something with interesting parts in it.

For Ozzy getting Geezer’s lyrics right wouldn’t always be easy. He certainly struggled on ‘Into The Void’. It has this slow bit, but then the riff where Ozzy comes in is very fast. Ozzy had to sing really rapidly: ‘Rocket engines burning fuel so fast, up into the night sky they blast’, quick words like that. Geezer had written all the words out for him.

‘Rocket wuhtuputtipuh, what the fuck, I can’t sing this!’

Seeing him try, it was hilarious.

Just like our previous albums Master of Reality had some controversial moments. ‘Sweet Leaf ’ upset some people because of the reference to drugs, and so did ‘After Forever’, thanks to Geezer’s tongue-in-cheek line ‘would you like to see the Pope on the end of a rope’. The cover was unusual again as well: this time it just had words in purple and black on a black background. Slightly Spinal Tap-ish, only well before Spinal Tap. Although this time we were allowed two weeks to record the album, what with Rodger Bain producing and Tom Allom engineering again, musically Master of Reality was a continuation of Paranoid. At the time I thought the sound could’ve been a bit better. That’s the thing when you’re a musician: you like things to be a certain way, to sound a certain way, and therefore it’s difficult to leave it up to other people. When it goes into somebody else’s hands you’ve got no control over it, and when you hear it it’s not like you expected it to be. That’s why I got involved more and more after those first albums.

26

No, really, it’s too much . . .

When we recorded Paranoid I still lived at home. My parents had bought another place in Kingstanding, near Birmingham. They planned to move there as soon as they got rid of the shop. Mum wanted to get out of it. It was just a burden. You’d wake up in the morning and the shop opened and after you closed you’d go to bed. They could never go away. We never went on a holiday as a family, they had never been abroad.

I was proud of that new place. Before they moved in I had a key and if I had met a girl I’d take her up there: ‘This is our new house!’

After all, I couldn’t take anybody back to the old house: ‘Here, come and sit on this box of beans, and I’ll get you a nice drink.’

Wouldn’t think of it.

But it was time for me to find my own place. At first I didn’t have the money to do that, and when the money came in I was out on tour all the time. The first big cheques went towards a flash car anyway. No sooner did I get my hands on some serious cash than I bought myself a Lamborghini. So here was this Lamborghini outside the house in Endhill Road, Kingstanding. The house cost £5,000 when they bought it; this thing was like five times more than that. That car outside, we were mad in those days.

We were all car crazy. Geezer always said: ‘When I pass my test, I’m going to buy a Rolls-Royce.’

One day I came home, and there was this Rolls parked outside our house on Endhill Road. I thought, oh hell, he’s done it! Geezer’s passed his driving test! Bill also bought a Rolls-Royce. In the ownership book there was Frank Mitchell, the famous Mad Axeman, who killed a lot of people, Sir Ralph Richardson, the well-known actor, and then Bill Ward! He’d have crates of cider in the back of it, like a travelling bar. Ozzy didn’t have a driving licence, but he still bought my Rolls off me. His wife drove him and he came over to my house with all his dogs on the back seat. It was an immaculate car when I sold it to him, and the state of it when he came over! Dogs shitting in there and everything.

Geezer didn’t manage to keep his car in mint condition either. It was the days of platform shoes, and Geezer’s were very, very big. How on earth he drove that car with them I just don’t know. He was driving around Devon, where the hills are quite steep, and he stopped off at a shop that was on top of one of these hills. He parked the car, went in on his platform shoes, and somebody in the shop suddenly said: ‘Look! There’s a car rolling down the hill. And it’s a Rolls-Royce!’

Geezer went: ‘Oh my God!’

He ran out, hobbling along on his platform shoes as fast as he could, trying to get next to his car so that he could open the door and stop it. Of course Geezer couldn’t keep up with it and the car went flying down the hill and crashed through a fence, straight into a tree. On his way home he drove past my house, and I heard his car go ‘kchh, kchh, kchh’, this scraping sound of the fan hitting the radiator. The front was completely smashed up, and Geezer said to me: ‘Now I see why they call it a Rolls . . .’

I bought my first house in 1972 in Stafford, north of Birmingham. It was a three-acre property with a swimming pool. I soon noticed that they were building this modern house right behind it and I thought, fuck, it’s right behind my swimming pool! Instead of allowing it to bother me, I bought it for my parents. They moved in there from their house in Kingstanding. It was a lovely place, brand new, all carpeted, modern bathrooms, the whole lot. I let Dad use some of the land where he could have his chickens, so he quite liked it there. But Mum felt like she was stuck in the middle of nowhere, too far away from the city. It was brilliant giving them that first house, but they didn’t like it, so that was a huge disappointment to me. I said: ‘Okay, you find yourselves a house you do like and I don’t want anything to do with it. You tell me about it and I’ll get it.’

So they did. They found this house that they liked at an auction. I was in America at the time, so I sent this guy along to bid for this place. And who was he bidding against? My aunt, who was trying to get it as well! I didn’t find out till afterwards. It was just the two of them bidding. I couldn’t believe it! But we got it in the end and they were absolutely thrilled to live there. Dad had horses and chickens there, so he was in his element. It was almost too late for him, because he was starting to get too ill to enjoy it, but he did have a few good years there.

I tried to look after them, but that wasn’t easy. Earlier, when we lived in Kingstanding, I saw my father outside with this old handle trying to crank-start his car and I thought, oh God, every morning he’s out there doing it, cigarette in his mouth, really horrible, we can’t have this. So I bought him a Roll-Royce. Mum said: ‘He’s not going to like that!’

‘Of course he will!’

I went to this dealership and bought him a Rolls-Royce for his birthday. They delivered it to the house with a crate of champagne in the back. Dad just went: ‘What’s that? I don’t want that! Can you imagine me going to work in that? What would all the people say, and the neighbours, what are they going to think? Me with a Roll-Royce!’

Bloody hell. I had to phone the Rolls-Royce people up and say: ‘He doesn’t want it.’

‘What do you mean he doesn’t want it? It’s a Rolls-Royce!’

‘Yes, but he won’t even get in it.’

So they came and picked it up. I said to Dad: ‘What do you want then?’

‘I don’t want anything.’

‘Wouldn’t you be better off with another car? What about a Jaguar?’

‘Well, it’s better than that thing.’

So I bought him this Jaguar 3.4, the classic one with all the nice wood and switches and stuff. He still didn’t want it, but I said: ‘Dad, you got to have it. I ca

n’t get my money back now. I bought this car; they won’t just forget about it, I have to buy something off them.’

He used that for a while, but it was a struggle. I thought, blimey, I try and help him out and he says: ‘I don’t want that bloody thing.’

My father died in 1982, he was only about sixty-five years old. Mum survived him by nearly fifteen years. He was a stubborn man, very proud, and he never complained. He’d just plod on. He had worked hard all his life. That’s what he believed in, work and nothing but work. And he would never stop smoking. He smoked himself to death. He died of a collapsed lung and of emphysema.

One day I noticed he was looking ill. Because Sabbath had done some charity work for the hospital in Birmingham I had met these specialists. I told them about Dad and they said: ‘Well, get him to come in.’

Dad hated doctors, so I said: ‘There’s no way he’s coming to hospital. Would you come out and see him?’

They did and he went absolutely mad. He hit the roof, going: ‘Don’t you ever bring them around here again!’

They checked him over anyway and said: ‘Well, he’s in a bad way.’

But there was nothing you could do for him, he just wouldn’t have it.

Couldn’t buy him a house, couldn’t buy him a car . . . couldn’t buy him his health.

27

White lines and white suits

In England it was all hash and dope and pills, but when we headlined the Los Angeles Forum in the autumn of 1971 I was introduced to cocaine. I said to one of our roadies: ‘I feel really tired.’

He said: ‘Why don’t you have a little line of coke?’

‘No, I don’t want to do any of that.’

He was American, so he was familiar with it. He said: ‘You’ll be fine. Just have a little toot before you go on.’

I had a toot and I thought, ah, this is wonderful! Let’s get on stage and play! And that was it. Bloody hell! I felt great on stage and of course the next time I had a little bit of that stuff before going on again. And then I started doing it more and more. As you do.

To do something special around that gig we also performed at the Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Strip. Patrick Meehan said: ‘Why don’t we wear something different? White suits and top hats and canes!’

We hired all these white suits and they were absolutely covered in dirt after no time at all. Most people take these things back all nice on hangers, but the people at the rental place must have thought, who’s had these?

The Beach Boys came to see us that night and I didn’t know what they looked like. I was coming out of the dressing room and somebody walked up to me and said: ‘Can I come in and see the rest of the guys?’

‘No, no, there’s nobody allowed in the dressing room.’

It was a little bit embarrassing afterwards, when I found out he was a Beach Boy.

LA and movie stars and sunshine – it made quite an impression on us. We ended up at these well-to-do parties where we saw lots of movie stars, like Tony Curtis and Olivia Newton-John. We’d be coked out anyway, as a lot of them were as well. Floating around there . . .

I think it was at the end of that third tour of America that we played the Hollywood Bowl for the first time. My memory is not crystal-clear about that show, because I collapsed at the end of it. I passed out because of exhaustion. I just remember going to the last song and then urrrggh, boing, and gone. The doctor who examined me said: ‘You’ve got to go on the next plane back to England, go straight home and just take it easy.’

I was about to have a nervous breakdown, so they prescribed Valium in high doses. I was a fucking zombie all day. I really had to just rest. It had been too much with the lifestyle we were living, all the touring and not getting a lot of sleep. And the drugs, I suppose. Bill was diagnosed with hepatitis and ended up in hospital. He carried this rusty knife with him all the time and he opened some clams with it and cut his hand. He claims he got it either from his knife or from a shell. Being a vegan, Geezer couldn’t get half the food he wanted, so a combination of that and drugs made him awfully thin. He got these kidney stones and ended up in hospital as well. We were all falling to bits. Ozzy probably had the most unhealthy lifestyle of all of us, but he was the only one still standing.

We were all out for the count, but Ozzy? He was right as rain.

28

Air Elvis

We started off 1972 with a nineteen-day UK tour with Glenn Cornick’s band Wild Turkey. We had them supporting us, because Patrick Meehan had teamed up with Brian Lane and they managed the band. Lane was the manager of Yes, which was why we had them on the next tour with us: thirty-two shows throughout the States and Canada, starting in March, the Iron Man tour. Us and Yes: it was an extremely unlikely combination. They hated us, because I’m sure in their minds they were the clever players and we were the working class. Sometimes they talked and other times they would walk straight past you. Very strange. Years later we all got along fine, but it took a long time. And they were funny on stage. If anyone made a mistake, the daggers would be out. We thought, what’s all that about? Music, somebody’s made a mistake, so what? It’s a good thing they weren’t in our band. We would make mistakes every two minutes. Here we were, with them as supporting act with all their clever stuff coming out, and we’re going ‘boing’, ‘clunk’, ‘zzzzz’. They must have gone: ‘What the fuck? What are we doing here?’

Their keyboard player, Rick Wakeman, didn’t get on with them, so he travelled with us as much as he could. We liked Rick. I think he was interested in playing with us, but he would have been too good, too much for what we wanted. We only wanted something very basic, that just went ‘duh-duuh-duh’. It wasn’t like Yes music.

On our previous tour one night, Elvis was staying at the same hotel we were at. We would see him come in with all this security and go to the top floor. We were invited to go and see Elvis perform. I had a bird that night, so I said: ‘I’m not going.’

I regretted that afterwards, because I didn’t see his show then and I never would.

On this tour we flew from LA to Vegas and back in a plane that belonged to Elvis. Really strange: all leopard-skin seats in there, very flash. The stewardess on the plane came out with a plate of all different coloured sandwiches. I went: ‘Blimey. What’s this then?’

‘Well, it’s coloured bread.’

‘Ah!’

It must have been something that Elvis liked. But it was a nice plane. We used it, behaved ourselves, left it in one piece as, of course, we were very respectful. I mean, it was Elvis!

29

Going Snowblind

We took quite a long time to write and rehearse for the Volume 4 album. It’s not like it was becoming harder to come up with stuff, but the pub was only a mile away, so we’d start to come up with ideas, and it was: ‘Ah, oh . . .’

And they’d all go down to the pub for ‘a’ drink.

I’d think: I’m not going to go; I’ll just sit here and try to come up with something. I’d play for a bit, an hour, two hours, three hours, and they’d all come back plastered: ‘You got anything?’

Oh, great! I felt really pressured.

When it was suggested we go to the States to record, we were all very much in favour of the idea. It was a way to avoid the English taxman and the studio rates were better, cheaper, out there as well. More important than that, we thought it would be nice to really go somewhere else to try and get a different vibe. We went to Los Angeles in May 1972. Patrick Meehan knew John Dupont, from the Dupont company, lighters and paints and all that. A big – huge – company. We rented his house in Bel Air. It was a great place with a big ballroom-type room overlooking the pool. It had a magnificent view of LA, the works. We all lived together there, the band, Meehan and these two French au pair girls who came with the house.

The vibe in America was great. The Record Plant, where we recorded, was a state-of-the-art studio and far better than what we were used to. We decided to produce Volume 4 ourselves. It’s not li

ke we were fed up with Rodger Bain or anything, I thought he was all right. But we had done so much studio work by then, that we felt we knew how to do it ourselves. I’ve heard Rodger has since disappeared and won’t talk to anybody any more. I don’t get that. I wonder why that would be.

Patrick Meehan put himself down as producer as well. I don’t know why he did that either. But he was there, he was in the control room and I suppose he thought, oh I’ll just add my name to it. Once or twice he may have said: ‘What if we try . . .?’ and that was it, his part in the production.

Producing it ourselves was everybody going: ‘I want my bass up’, or ‘I want this’ and ‘I want that’, but it worked out okay. It was only later, from Sabbath Bloody Sabbath and onwards, that I started really poking my nose in more.

Recording took six weeks, maybe even two months. During that time we also set some gear up at the house in Bel Air, where we wrote the last of the songs. It was a different environment, everybody had a brighter attitude and there was a schedule: ‘We have got to get it done.’

We were still fucking about and doing stupid jokes, but ideas and the songs were coming out quickly. Perhaps having loads of cocaine helped speed things up as well. And we had a lot of it. It came in a sealed box the size of a speaker, filled with files all covered in wax. You’d peel the wax off and it was pure, fantastic stuff and loads of it. It was like Tony Montana in the movie Scarface: we’d put a big pile on the table, carve it all up and then we’d all have a bit, well, quite a lot. Word got around, and soon other musicians, lots of women and new ‘friends’ came to the house and everybody was diving in.

One sunny day we were sitting in the TV room around a table with cocaine tipped out on it and grass as well. This house had all these buttons around all the rooms. Bill thought it was the maid’s button and pressed it, but it was an alarm button for the fucking Bel Air police. Only a few minutes after that I stood up, looked out of the window and there were about six or eight police cars in our drive. I shouted: ‘Quick, the police!’

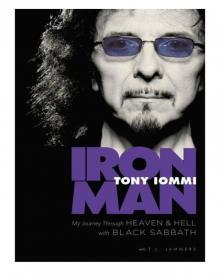

Iron Man

Iron Man