- Home

- Tony Iommi

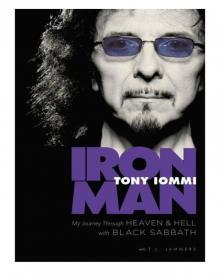

Iron Man

Iron Man Read online

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Introduction

Chapter 1 - The birth of a Cub

Chapter 2 - It’s the Italian thing

Chapter 3 - The shop on Park Lane

Chapter 4 - The school of hard knocks

Chapter 5 - Out of The Shadows, into the limelight

Chapter 6 - Why don’t you just give me the finger?

Chapter 7 - A career hanging off an extra thin string

Chapter 8 - Meeting Bill Ward and The Rest

Chapter 9 - Job-hopping into nowhere

Chapter 10 - How three angels saved heavy metal

Chapter 11 - Things go horribly south up north

Chapter 12 - Down to Earth

Chapter 13 - A flirt with Tull in a Rock ’n’ Roll Circus

Chapter 14 - The early birds catch the first songs

Chapter 15 - Earth to Black Sabbath

Chapter 16 - Black Sabbath records Black Sabbath

Chapter 17 - Now under new management

Chapter 18 - Getting Paranoid

Chapter 19 - Sabbath, Zeppelin and Purple

Chapter 20 - This is America?

Chapter 21 - Happy birthday witches to you

Chapter 22 - Ozzy’s shockers

Chapter 23 - An Antipodean murder mystery

Chapter 24 - Flying fish

Chapter 25 - Number 3, Master of Reality

Chapter 26 - No, really, it’s too much . . .

Chapter 27 - White lines and white suits

Chapter 28 - Air Elvis

Chapter 29 - Going Snowblind

Chapter 30 - This is your captain freaking . . .

Chapter 31 - A rather white wedding

Chapter 32 - Going to the big house

Chapter 33 - One against nature

Chapter 34 - The well runs dry

Chapter 35 - Sabbath Bloody Sabbath

Chapter 36 - The California Jam

Chapter 37 - Where did all the money go?

Chapter 38 - Everything’s being Sabotaged!

Chapter 39 - Bruiser in a boozer

Chapter 40 - Me on Ecstasy

Chapter 41 - Ecstasy on tour

Chapter 42 - We Never Say Die

Chapter 43 - Ozzy goes

Chapter 44 - Susan’s Scottish sect

Chapter 45 - Dio does but Don don’t

Chapter 46 - Bill goes to shits

Chapter 47 - Heaven and Hell

Chapter 48 - Ignition

Chapter 49 - Vinny says Aloha

Chapter 50 - Getting Black and Blue

Chapter 51 - Melinda

Chapter 52 - Friends forever

Chapter 53 - The Mob Rules

Chapter 54 - The Mob tours

Chapter 55 - A Munster in the mix

Chapter 56 - To The Manor Born Again

Chapter 57 - Size matters

Chapter 58 - Last man standing

Chapter 59 - The mysterious case of the lofty lodgers

Chapter 60 - Lovely Lita

Chapter 61 - Together again, for a day

Chapter 62 - Twinkle twinkle Seventh Star

Chapter 63 - Glenn falls, but there is a Ray of hope

Chapter 64 - The quest for The Eternal Idol

Chapter 65 - Taxman!

Chapter 66 - Headless but happy

Chapter 67 - Oh no, not caviar again!

Chapter 68 - TYR and tired

Chapter 69 - It’s Heaven and Hell again

Chapter 70 - Bound and shackled

Chapter 71 - In harmony with Cross Purposes

Chapter 72 - The one that should’ve been Forbidden

Chapter 73 - Flying solo with Glenn Hughes

Chapter 74 - Living apart together

Chapter 75 - The love of my life

Chapter 76 - Reunion

Chapter 77 - Cozy’s crash

Chapter 78 - Bill, Vinny, and Bill and Vinny

Chapter 79 - Belching after a Weenie Roast

Chapter 80 - Iommi, the album

Chapter 81 - An audience with the Queen

Chapter 82 - Hats off to Rob Halford

Chapter 83 - Fused with Glenn again

Chapter 84 - Entering the Halls of Fame

Chapter 85 - This is for peace

Chapter 86 - Heaven and Hell, tour and band

Chapter 87 - The Devil You Know

Chapter 88 - Farewell to a dear friend

Chapter 89 - Not a right-hand man

Chapter 90 - A good place

Acknowledgments

Index

Copyright Page

I dedicate this book to Maria; my wife and soulmate.

My daughter Toni, for being the best daughter

any man could ever have.

My late Mom and Dad, for giving me life.

Introduction:

The Sound of Heavy Metal

It was 1965, I was seventeen years old, and it was my very last day on the job. I’d done all sorts of things since leaving school at fifteen. I worked as a plumber for three or four days. Then I packed that in. I worked as a treadmiller, making rings with a screw that you put around rubber pipes to close them up, but that cut up my hands. I got a job in a music shop, because I was a guitarist and played in local bands, but they accused me of stealing. I didn’t do it, but to hell with them: they had me cleaning the storeroom all day anyway. I was working as a welder at a sheet-metal factory when I got my big break: my new band, The Birds & The Bees, were booked for a tour of Europe. I hadn’t actually played live with The Birds & The Bees, mind you; I’d just auditioned after my previous band, The Rockin’ Chevrolets, had hoofed out their rhythm guitarist and subsequently broken up. The Rockin’ Chevrolets had been my first break. We wore matching red lamé suits and played old rock ’n’ roll like Chuck Berry and Buddy Holly. We were popular around my hometown of Birmingham, and played regular gigs. I even got my first serious girlfriend out of that band, Margareth Meredith, the sister of the original guitarist.

The Rockin’ Chevrolets were fun, but playing in Europe with The Birds & The Bees, that was a real professional turn. So I went home for lunch on Friday, my last day as a welder, and said to my mum: ‘I’m not going back. I’m finished with that job.’

But she insisted: ‘Iommis don’t quit. You want to go back and finish the day off, finish it proper!’

So I did. I went back to work. There was a lady next to me on the line who bent pieces of metal on a machine, then sent the pieces down to me to weld together. That was my job. But the woman didn’t come in that day, so they put me on her machine. It was a big guillotine press with a wobbly foot pedal. You’d pull a sheet of metal in and put your foot on the pedal and, bang, a giant industrial press would slam down and bend the metal.

I’d never used the thing before, but things went all right until I lost concentration for a moment, maybe dreaming about being on stage in Europe and, bang, the press slammed straight down on my right hand. I pulled my hand back as a reflex and the bloody press pulled the ends off my two middle fingers. I looked down and the bones were sticking out. Then I just saw blood going everywhere.

They took me to hospital, sat me down, put my hand in a bag and forgot about me. I thought I’d bleed to death. When someone thoughtfully brought my fingertips to hospital (in a matchbox) the doctors tried to graft them back on. But it was too late: they’d turned black. So instead they took skin from one of my arms and grafted it on to the tips of my wounded fingers. They fiddled around a bit more to try to ensure the skin graft would take, and that was it: rock ’n’ roll history was made.

Or that’s what some people say, anyway. They credit the loss of my fingers with the deeper, down-tuned sound of Black Sabbath, which in turn became the template f

or most of the heavy music created since. I admit, it hurt like hell to play guitar straight on the bones of my severed fingers, and I had to reinvent my style of playing to accommodate the pain. In the process, Black Sabbath started to sound like no band before it – or since, really. But creating heavy metal because of my fingers? Well, that’s too bloody much.

After all, there’s a lot more to the story than that.

1

The birth of a Cub

Of course, I wasn’t born into heavy metal. As a matter of fact, in my first years I preferred ice cream – because at the time my parents lived over my grandfather’s ice cream shop: Iommi’s Ices. My grandfather and his wife, who I called Papa and Nan, had moved from Italy to England, looking for a better future by opening an ice cream business over here. It was probably a little factory, but to me it was huge, all these big stainless steel barrels in which the ice cream was being churned. It was great. I could just go in and help myself. I’ve never tasted anything that good since.

I was born on Thursday 19 February 1948 in Heathfield Road Hospital, just outside Birmingham city centre, the only child of Anthony Frank and Sylvie Maria Iommi, née Valenti. My mother had been in hospital for two months with toxaemia before I appeared; was this a sign of things to come she might have felt! Mum was born in Palermo, in Italy, one of three children, to a family of vineyard owners. I never knew my mum’s mother. Her father used to come to the house once a week, but when you’re young you don’t hang around sitting there with the old folks, so I never knew him that well.

Papa on the other hand was very good natured and generous and as well as giving money to help the local kids he’d always hand me half a crown when I came to see him. And some ice cream. And salami. And pasta. So you can imagine I loved visiting him. He was also very religious. He went to church all the time and he sent flowers and supplies over there every week.

I think my nan was from Brazil. My father was born here. He had five brothers and two sisters. My parents were Catholic, but I’ve only seen them go to church once or twice. It’s strange that my dad wasn’t as religious as his father, but he was probably like me. I hardly ever go to church either. I wouldn’t even know what to do there. I actually do believe in a God, but I don’t go to church to press the point.

My parents worked in a shop that Papa had given them as a wedding present, in Cardigan Street in Birmingham’s Italian quarter. As well as the ice-cream factory, Papa owned other shops and he used to have a fleet of mobile baking machines. They’d go into town, set up and sell baked potatoes and chestnuts, whatever was in season. My dad was also a carpenter and a very good one at that; he made all our furniture.

When I was about five or six we moved away from ice-cream heaven to a place in Bennetts Road, in an area called Washwood Heath, which is part of Saltley, which in turn is a part of Birmingham. We had a tiny living room with a staircase going up to the bedroom. One of my earliest memories is of my mother carrying me down these steep stairs. She slipped and I went flying and, of course, landed on my head. That’s probably why I am like I am . . .

I was always playing with my lead soldiers. I had a set of those and little tanks and so on. As a carpenter my dad was away a lot, building Cheltenham Racecourse. Whenever he came back home he’d bring me something, like a vehicle, adding to the collection.

When I was a kid I was always frightened of things, so I’d get under the blanket and shine a little light. Like a lot of kids do. My daughter was the same. Just like me, she couldn’t sleep without the light on, and we’d have to keep her bedroom door open. Like father, like daughter.

One of the reasons I grew a moustache in later years was because of what happened to me in Bennetts Road one day. There was a guy up the road who used to collect great big spiders. I don’t mind them now, but I was very much afraid of them then. I was eight or nine at the time. This guy was called Bobby Nuisance, which is the right name for him, and he chased me with one of his spiders once. I was shitting myself and running down this gravel road when I tripped, so all the gravel went into my face and along my lip. The scar is still there now. The kids even started calling me Scarface, so I got a terrible complex about that.

I did have another scar there as well, because not long after the spider thing somebody threw a firework, one of those sparklers, and it went straight up my face. Over the years the scars disappeared, but the one on my lip still stuck out when I was young, so as soon as I could I grew a moustache.

Still living in Bennetts Road I joined the Cubs. It’s like the Scouts. The idea was that you’d go on trips, but my parents didn’t want me to go away. They were very protective of me. Also these trips cost money and we didn’t have that; they earned a pittance in those days. I did wear a Cubs uniform: little shorts and the little thing over the socks, a cap and a tie. So I looked like a younger version of Angus Young.

With scars.

2

It’s the Italian thing

I did get some emotional scars as well. I know Dad didn’t want me, I was an accident. I even heard him say this in one of his screaming moods: ‘I never wanted you anyway!’

And there was a lot of screaming, because my parents used to fight a lot. He’d lose his temper and Mum’d lose hers, because with him the Italian thing would come out and she was very wild anyway and she’d go potty. They’d grab each other’s hair and really seriously fight. When we lived in Bennetts Road I actually saw my mother hit Dad with a bottle and him grabbing her hand trying to defend himself. It was bloody awful, but the next day they’d be talking away like nothing had happened. Really peculiar.

I remember them fighting with the next-door neighbours as well. Mum was in the backyard and there was a wooden fence between us and the neighbours. Apparently one of them said something bad about our family and mother went into a rage. I looked out of my bedroom window and I saw her hanging over the fence hitting the neighbour lady over the head with a broom. And then Dad got involved and so did the woman’s husband and it was a fight over the fence until the fence came down. I saw them screaming and shouting and hitting each other and I just stood there, looking out of my first-floor window, crying.

If I did anything wrong I would cop the brunt of it as well. I was frightened to do anything, always afraid of getting beaten up. But that’s how it was in those days. It happened with a lot of families, people fighting and getting hit. It probably still is that way. Dad and me didn’t get on that well when I was young. I was the kid who was never going to do any good. It was always: ‘Oh, you haven’t got a job like so-and-so has got. He is going to be an accountant and what are you going to do?’

I was belittled by him all the time, and then Mum joined in as well: ‘Yeah, he’s got to get a bloody job or he’s out!’

It is one of the reasons I wanted to be successful, if only to show them.

Growing up and getting older, there came a point where I would not accept getting clipped around the earhole any more. One time I was on the couch and Dad was hitting me, and I grabbed his hands and stopped him. He went mad, almost to the point of crying: ‘You don’t do that to me!’

That was awful. But he never hit me again.

I must have been nine or ten when I saw my grandfather die. He was at home, very ill, when he went unconscious. He was in bed and my job was to watch him to see if he came round. I’d sit there, mopping his face, and Dad would pop in now and again. But I was alone with him when he got the ‘death rattle’. He made this choking, gurgling sound and then he died. I felt really sad but it was also frightening. I saw the family coming in and out and they all seemed a bit afraid as well.

I’ve seen one or two people die since then. About twenty-five years ago this old lady, very well dressed and very well spoken, lived across the road from me. She went by a nickname, Bud; even her daughter called her that. I went over there once a week to see her and then she’d say: ‘Oh, you know, let’s have a brandy.’

One day her daughter came rushing over to my house, scr

eaming: ‘Quick, come over, come over!’

I went over and found Bud passed out on the floor. I lifted her up a bit, took her in my arms and I shouted: ‘Call an ambulance!’

Her daughter ran off, and at that moment Bud died, right there in my arms. It was the same thing: the choking, gurgling sound and . . . bang. As soon as that happened, it brought me immediately back to my grandfather.

I sat there with her until the ambulance showed up. After that I could smell her perfume everywhere and I could never smell that perfume again. For me it had turned into the smell of death.

3

The shop on Park Lane

When I was about ten we moved to Park Lane in Aston. It was an awful, gang-infested, rough part of Birmingham. My parents bought a sweet shop there, but soon they also sold fruit and vegetables, firewood, canned foods, all sorts of stuff. We’d get people knocking on our door in the middle of the night: ‘Can we buy some cigarettes?’

With a shop like that, you basically never closed.

The shop had everything people needed, but it also turned into a meeting place. Some of the neighbours would always be on the step, gossiping away: ‘Have you seen so-and-so down the road, ooh, she’s wearing a new . . .’

Et cetera. Sometimes they wouldn’t even buy anything and stand there for hours, talking. And Mum would be behind the counter, listening.

My mother ran the shop, because Dad worked at the Midlands County Dairy, loading the trucks with milk. He needed to do that to supplement the family income, but I also think he did it because there he was around people he liked. Later on he bought a second shop in Victoria Road, also in Aston, where he started selling fruit and vegetables.

My parents liked Aston, but I didn’t. I hated living in the shop because it was damp and cold. It was only a two-bedroom house, with the lounge downstairs, a kitchen and then, outside in the backyard, the toilet. You couldn’t bring friends there, because our living room doubled as the stockroom: it was filled with beans and peas and all the tinned stuff. That’s how we lived. You were surrounded by bloody boxes and shit all the time.

Iron Man

Iron Man